Being told you only have months to live due to terminal lung cancer that has spread to other parts of your body is confronting.

It focuses attention. Raises expectations. Opens questions. What’s important to do before my life passes on?

For an adopted person finding them self in this challenging, irreversible position exposes unfinished business, taking them to the very beginning of their lives as they fast approach the very end.

William Hammersley-Ellis is in this situation.

When he dies he wants his correct identity on his birth and death certificates not the legally constructed person—John XXX XXX*—created via his adoption order.

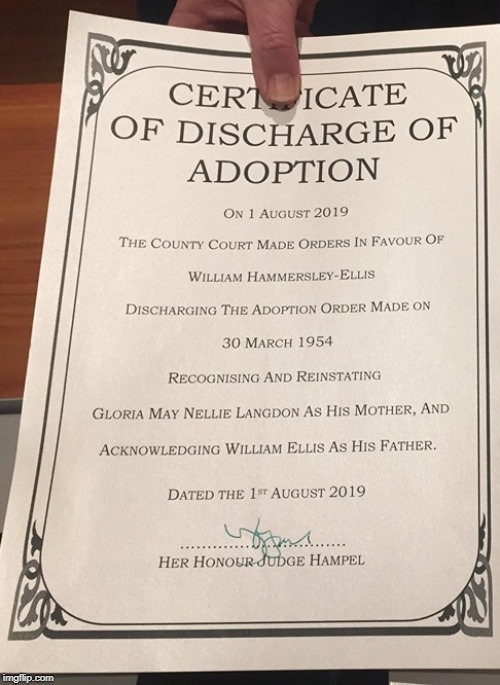

To this end William recently applied to the Melbourne Country Court to have his adoption order discharged.

To rightfully restore his true identity erased, without his consent, 67 years ago, when his adoption order sealed his original birth certificate and was substituted with new document that created a falsehood, of being born to a selected couple when he was the indivisible progeny of another.

His request to the Court very clear: ‘I ask the Court to order Births Deaths and Marriages to issue me with a new birth certificate reflecting the truth. On this new birth certificate, I want my name to be shown as William Hammersley-Ellis. I cannot change the past, and neither can the Court. I don’t ask the Court to rewrite history but I do ask the Court to restore the truth about who I am. I simply want to be me, and to be part of my family tree – regardless of whether any of my family have anything to do with me or not.’

Losing one’s identity, family and inter-generational heritage at birth, together with sealed records, the burden of secrecy and weight of not knowing the truth, creates a bewildering vacuum for the adopted child.

They are hard beginnings to grow into or out of.

Add a struggling household and repeated beatings and this start to life is a sequence of ongoing trauma and suffering.

William was dealt the weakest deck of cards imaginable — the loss of his mother and family at birth; a purchased baby (evidence of illegal monetary exchanges during his adoption process); the recipient of harsh beatings at the hand of his adoptive father; and, as a young boy at youth club, been sexually abused on a regular basis by the incumbent priest.

These harmful events spiralled him into teenage meltdown.

Leaving home, he gave up school, turned to substance abuse, self harmed, turned violent and questioned his own sexuality. A damaging pattern that continued throughout his 20s and 30s, made worse by being unable to maintain close relationships.

Adopted boys with this type of start in life often become angry, violent men. William acknowledges he was a young man fuelled by anger.

He was angry with his mother for not keeping him; for giving him away. Angry at his second family for not understanding his loss, their hand-to-mouth existence and beating him in an attempt to keep him on track. Angry for not being able to fit in, not knowing who he was, of where he belonged. Angry at being unable to express his pain or find help.

William’s life epitomised all that was dark and dangerous with closed adoption. No way out and no place to turn. With an alienated self and disconnection emerged a deep loneliness that became a lived pattern magnified one day, or numbed the next, by excessive use of alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana.

Falling into a deep, black hole had one benefit, he couldn’t sink any deeper.

William got lucky he found Kay, a loving partner who accepted him for who he is, supported him, stood by him. Together they had a son, created a family, they grew together, remained intact.

A life saver for William.

The birth of his son in his 40s reignited the flames of his own missing personal history. The pull to know more became stronger. With the help of an adopted sister he found his mother’s family, only to learn she had died a year before.

The impact: abandoned for a second time, the first loss unresolved. His uncertain past, deep hurt and volatile anger a wedge inhibiting any close connection between his new found kin, that included two half-siblings.

They drifted apart. The years drifted by. William’s attention focused on his immediate family, Kay and his son. On operating a florist.

For William many unanswered questions remained. Why did my mother agree to my adoption? Who is my father? What happened to him?

Momentum changed for William, and many others affected by adoption— mothers, fathers and their children—during the period 2009-2013 with the Federal Senate Inquiry into Forced Adoptions and the succession of State Apologies and the National Apology that followed.

Attending the Victorian Apology in Melbourne, a torrent a tears—restrained for so long—flowed from William as he viewed row upon row of children’s shoes placed on the steps of the Parliament. He was no longer alone. Others had suffered a similar fate. The walls of secrecy and silence had began to be broken down.

Linking up with mothers whose babies were taken without consent and with these babies, now adults, emerging from the shadows of confused lives to seek answers and redress, William began a two-year period of intensive research activity, sifting through archives, newspapers and engaging with others to patch together his early life, uncovering a clandestine baby trade operating out of the private maternity hospital where he began his life.

Exhausting all leads through paper records and personal conversations, he turned to DNA tests and analysis to offset the frustrating blockages of missing documents or family and their friends who remained tight lipped, intent on withholding critical personal information.

Success.

A precise DNA match leading to his father—deceased—but a surviving aunt (father’s sister) and cousins. In July this year a road trip to meet them; photographs to affirm genetic mirroring; a father’s grave to visit; a distant family to reconnect with.

Confirmation his father and mother were essentially good people trapped by circumstance, by the weight of social norms that limited choice, changing their lives and William’s, forever.

Back to court and William’s submission:

“I hate being adopted with every fibre of my being. It is like someone has branded me a less than worthy human and I want to be rid of this branding. I hate having to tell people that I am adopted. I am sick of the shame and the social stigma that goes with it. I don’t want to live as an adopted person. I don’t want to die as an adopted person. I just want to be a normal person, like everyone else, with a birth certificate that shows who their parents are.”

In an act of personal empowerment, William shed a life time of shackles of being invisible, voiceless, silenced. He represented himself. Doing so as an adopted person, an adult, a victim, who wanted one simple thing: to be formally recognised as the person he was born as, supported by an original birth certificate.

To discharge his adoption.

Connecting the dispersed pieces of his personal life he reminded the judge of his past history, of his rights under the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities and under various articles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by Australia in 1989. He drew attention to the wording in the Victorian Apology for Forced Adoption delivered on 25 October 2012 and the Federal Apology held in Canberra on 21 March 2013.

He emphasised how adoptees do not have a level playing field when it comes to their own identity. Discrimination prevents them from being able to make a choice about their true identity and to obtain a birth certificate that would reinstate their original identity.

He noted, “We (adoptees) are subject to a contract for life and beyond death to which we did not agree. For me, to exercise a choice to reclaim my identity and my ancestry I’ve lost (whether or not I have a social relationship with those of my family who are living) is of extreme importance to me and my children and my children’s children and generations to follow … as an adoptee, I am not equal before the law and am discriminated against because I cannot use my original birth certificates like everyone else. As an adoptee, I am legally prevented from identifying as the person I was when I was born, as is the right of every non-adopted person.”

He expressed his choice for a no fault, no fee, no fuss discharge of his adoption.

Judge Hampel granted his wish on 1 August 2019.

It is a momentous and significant legal decision. Adoption discharges are rare in Australia.

Not every adopted person will move to discharge their adoption but William’s case opens the door to ease the burden and simplify reasons for cause for those that do.

Adoptees wishing to follow his path should contact Adoptee Rights Australia (ARA), an organisation that stands for equal rights in law and policy for adopted people.

Victorious, William acknowledges and appreciates the support and assistance many individuals have given him to find out where he came from, to reconnect with missing kin and complete his sense of self. Life supporting pillars that help to diminish anger, allowing trust, joy and love to enter.

For William death is no more welcome than it ever was.

Dying, however, has shifted to a more peaceful pathway. There is comfort knowing he can leave with his original identity intact.

His sense of place—and of kin—restored, offering continuity and dignity to him and his family.

* Full name removed

Congratulations William, it is my extreme pleasure to call you my friend. You are an inspiration to other adoptees like myself. Your victory is a catalyst for the changes so many of us desire, the recognition that we are our own persons, we have our own biological identities, families, family histories, cultures etc that belong to us, not the state or any adoptive parents

I’m happy for William. Great article. I would certainly like a truthful birth certificate as was recommended by the senate inquiry.